Each floor erected in three and a half hours

The Kerrie Murphy Building at the International Grammar School (IGS) in Sydney is a simple building; one that does not boast to be better than its neighbors, but which causes gazes to linger anyway.

Designed by Allen Jack+ Cottier (AJ+C), the Kerrie Murphy Building at the International Grammar School (IGS) in Sydney was funded by the Building Education Revolution (BER) program, which aimed to provide new and refurbished halls, libraries and classrooms for primary schools. The architects recognized the potential of the IGS site, and proposed an ambitious four-story design that challenged city controls of allowing two stories on this site.

Genesis in brickwork

“Our research discovered that the neighboring building was only half a building, with keyed brickwork and blocked openings, anticipating a completion that never happened,” explains AJ+C CEO and design principal, Michael Heenan. “The city council agreed with our observations and approved the building in record time.”

Early in the design process, it became apparent to the design team that the new structure would have to respond to the precinct, Pyrmont, in which it is located. The identity of Pyrmont was founded on a powerful collection of 19th and early 20th century brick warehouse buildings, dictated by large brick planes with small openings, and regulated by the span of brick arches and arch bars.

Reinforcing the power, weight and strength of these brick warehouses, the new building has its genesis in the nature of brickwork, but ultimately uses precast for its simplicity and accuracy, as well as its effectiveness. These reasons were essential to ensuring the inner-city project could be completed quickly during the Christmas holidays without too much impact on the neighborhood.

Glass stuck to the concrete

The outer walls of the building are a combination of glass and raw, off-the-form precast concrete stained with a concrete stain. Embedded in the load-bearing, precast composite panels are 50 mm of high-density polystyrene with a 65 mm outer skin, and a 165 mm inner skin of structural concrete.

The window details were achieved in conjunction with 3M in Australia and the United States, but the glass was simply stuck to the concrete. “We believe this is the first time anywhere that VHB structural glazing tape has been used in this way to stick glass to a building. The punched through windows had to be very carefully executed to ensure there was no dilution of their ‘dew drop’ aesthetic,” Heenan says, referring to the high-performance bonding material that is typically used to attach glass to structural glazing frames, replacing structural silicone sealants. “We wanted the glass to look as if it was simply stuck to the concrete, with the almost ‘arrogant’ concrete not acknowledging the presence of the glass.”

The view from the streetscape of the building is nothing but concrete with holes punched through, with no evidence of the attachment of the glass. However, this appearance belies the enormous amount of testing and analysis that went into the development of the load-bearing pre-fabricated panels.

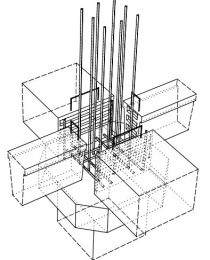

Building without internal columns

The team had to run and re-run a structural elemental analysis to achieve the desired efficiency and lightness of the wall panels, using normal reinforcing mesh with holes cut in. The building is made up of only four different pieces of concrete per floor, and repeats the front-wall panel, back-wall panel, curved stair-wall panel, and hollow-core floor panel – all load-bearing, with no internal columns.

The precast and preglazed panels were transported to site with all finishes complete, allowing the team to erect each floor in only three and a half hours, including the external and stair panels and flooring.

“The school was warned before the initial presentation that our design was an exercise in frugality. But to go from the initial idea to this level of clarity and simplicity took an enormous amount of drawing, analysis, testing and prototyping. Many hours were spent out at the concrete yard discussing and trying ideas,” notes Heenan.

Ecologically sustainable development

Sustainability was also a key factor in the design brief, and the new building had to satisfy the strict environmental controls imposed by the client, BCA Section J, and the 4 Star Green Star requirement imposed by the City of Sydney.

Ecologically sustainable development or ESD initiatives include a roof that is to become an outdoor playground shaded by an array of photovoltaic cells, while the building is able to produce its own power, collect its own water, and cool itself in a night purge. Despite the many fixed windows, which use the latest e-glass technology to maintain a high level of insulation, the building is also cross-ventilated with giant louvres at each corner.